Money & the World

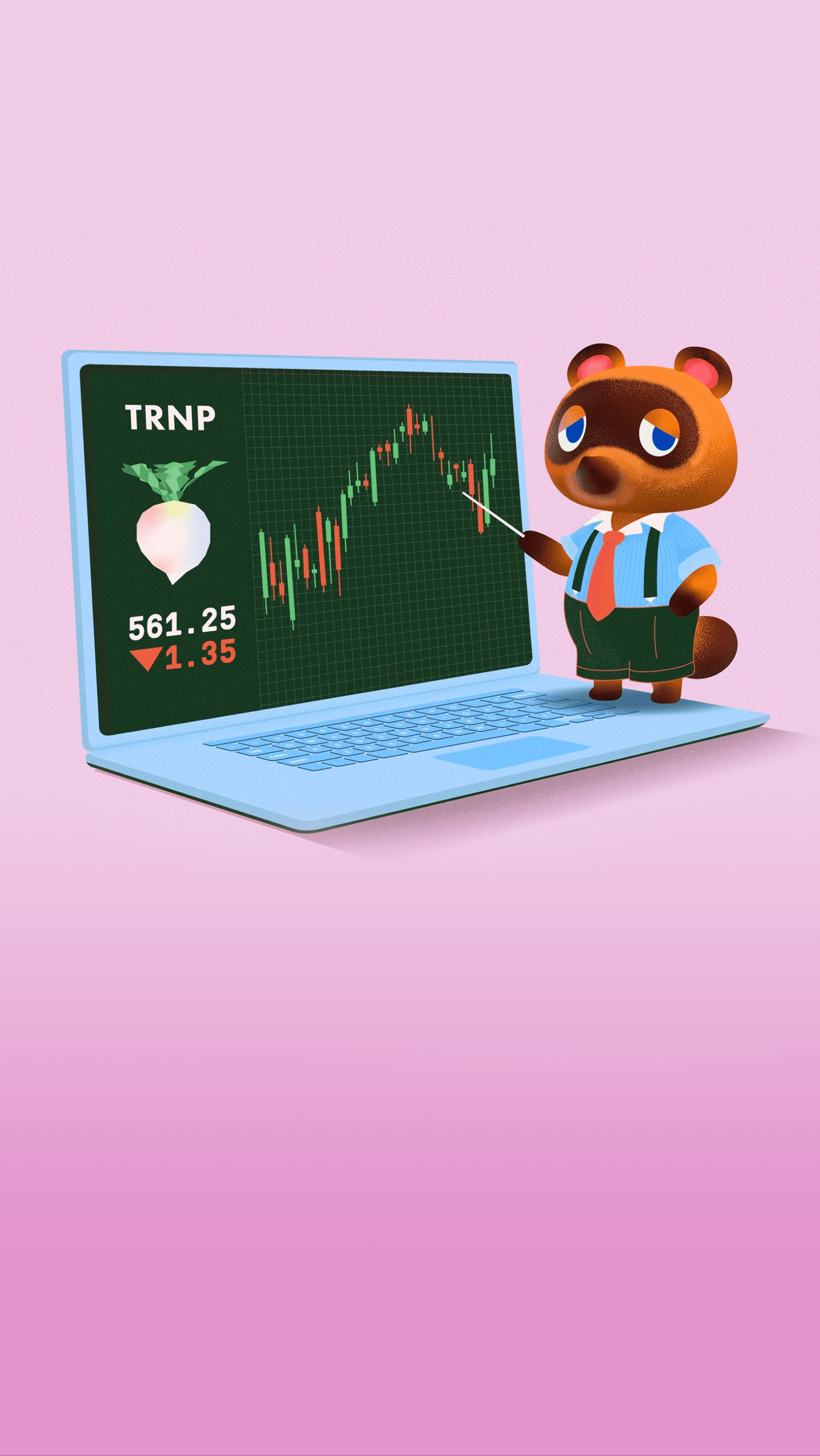

We Asked Our Resident Stock Market Genius About the Animal Crossing Economy

Is the economy built by the creators of Animal Crossing functional? Can you learn anything about the actual economy from it? Will a boar come and deliver turnips to us in real life anytime soon? We turned to Ben Reeves, CIO of Wealthsimple, to help us understand the world (both virtual and real).

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Animal Crossing: New Horizons launched at almost precisely the moment when millions of North Americans began to socially distance to slow the spread of Covid-19. Animal Crossing is a video game for the Nintendo Switch platform with the somewhat unlikely framing of navigating the economy of being a farmer, which didn’t stop it from becoming, as you likely know, the runaway hit video game of the month/year/epoch, and one of the prevailing memes of the crisis. Set on an idyllic tropical island, the game offers an escape from the pressures of quarantine life with its slow-paced cycle of landscaping, interior decoration, and trading gifts with imaginary animal buddies. It’s even possible to visit friends’ islands, offering a much-needed form of virus-free hanging out. If you have been on the internet you know that everyone has a “take” on it. I’d like to reassure you that I, in fact, do not have a take.

But what I wondered instead was: is this how an economy works? Because there’s a surprisingly sophisticated in-game economy — mortgages, savings accounts with changing interest rates, even a thriving stalk market that has spilled over into the real world (players who have great turnip rates on their island can offer access in exchange for real-life cash). Many players have managed to build small fortunes of “bells,” the in-game currency, by paying close attention to just how these systems work and exploiting that knowledge carefully. (The richest of them are known informally as bellionaires.)

To find out how realistic this economy is, and whether I could sort of use the game to understand the real actual economy (or even if there was anything the real economy could learn from the one in the game), I interviewed Ben Reeves, Wealthsimple’s Chief Investment Officer.

Have you ever played Animal Crossing?

No. I haven’t.

OK. Well, the game’s premise is that you've moved to a little island, you're fixing it up, and you're trying to entice other cute characters to move there. It’s mostly a lot of puttering around. But you're sort of building a tiny economy and there are rules inside of that economy.

There are rules, mostly unwritten, in our economy. So far, so good.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

There are even interest rates. One way you can make money as a player in the game is to deposit some bells (that's the currency) in a savings account in an in-game ATM. There's 0.5% interest rate. But what some players noticed was that the interest was compounded once a month, not daily. So you could deposit a chunk of money on the last day of the month and overnight you would wake up 0.5% richer. Could you do that in the real world? Just throw a ton of money into your savings account the day before it compounds?

No, no. Take a government bond, which is what a lot of money market accounts use. If you’re holding a government bond that’s going to be paying out in a month, you’re going to slowly see it approach the value of the payment.

A little trick like the one you describe in the game is called an arbitrage. A good way to think about this is that anywhere there's an obvious arbitrage like that, it will have ceased to exist. Those loopholes get closed. When there is one, people find it, they don't tell other people, but eventually people find out about it anyway and then it goes away. That's how markets work.

What about this. Some sneaky players deposit, say, 100,000 bells in their savings account. Then they set the clock on their Nintendo Switch a few years forward, open the game again, hit up the ATM and enjoy however many years of accumulated interest without having to actually wait for it to accrue. Nintendo ended up having to massively slash the interest rate to keep people from taking advantage of what I guess you would call “time travel arbitrage.”

I don’t know of anyone using a time travel arbitrage in the real world. I guess in video games sometimes you want to let people cheat and have fun and beat the game. I guess this one must have made the game less fun in the long term.

What was so strange was Nintendo was slashing interest rates at the exact same time that real-life interest rates were being slashed. But I suppose the rationale behind that was very different.

Unsurprisingly, you’re right. The real-life rate cut is more about the people who have loans. You want to keep the cost of servicing those debts down, because a lot of people’s incomes have been negatively impacted by the crisis, and central banks want people to have more money to meet their obligations and still spend to keep the economy alive. By injecting a bunch of money into the system, you're basically trying to keep high-interest debt from slowing down the economy, and to keep inflation down.

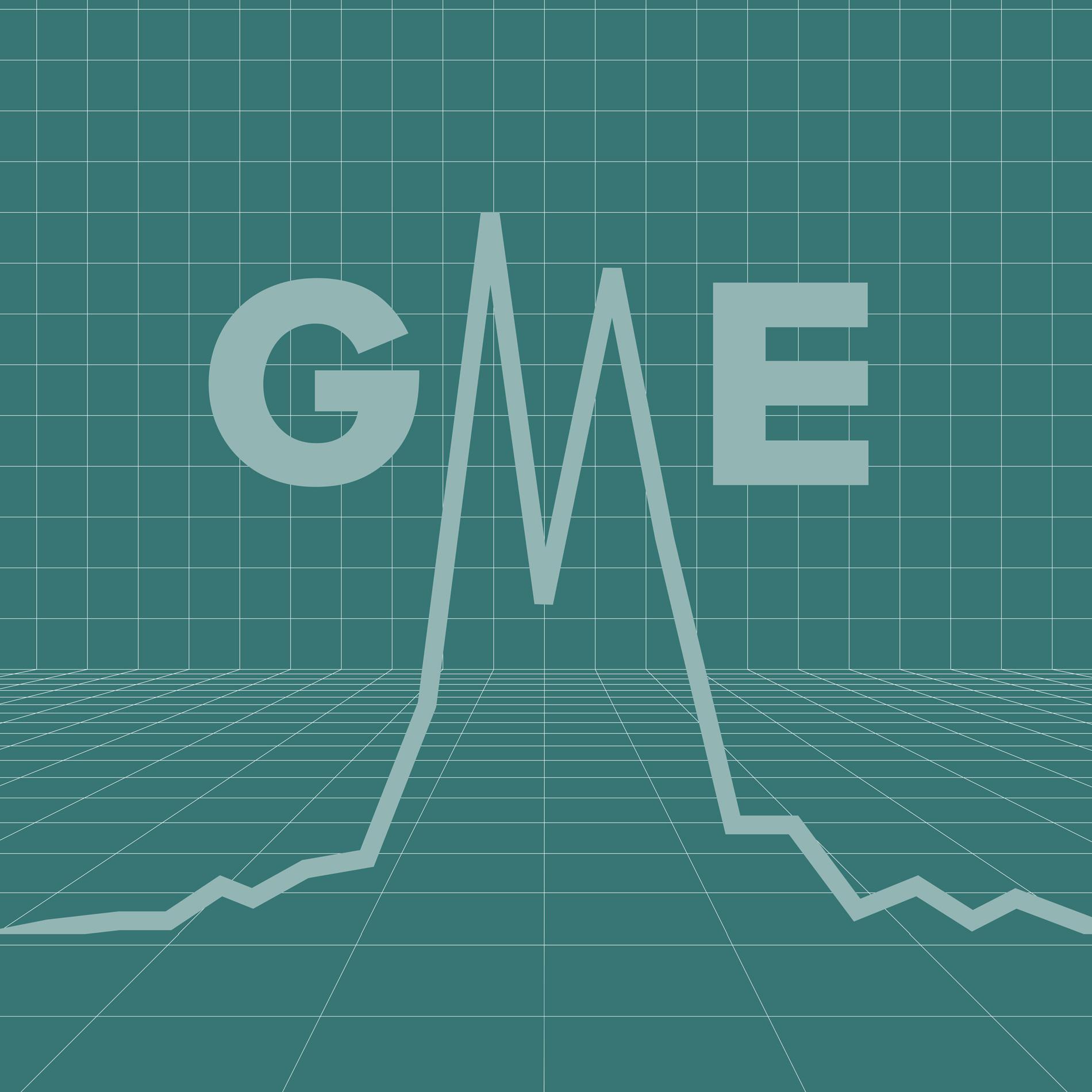

The other big way that people invest in Animal Crossing is called the Stalk Market. As in s-t-a-l-k. The way it works is that every Sunday morning a boar visits your island to sell turnips. You can buy as many turnips as you like from this turnip boar for a fixed price, usually around 100 bells for every 100 turnips. Then, throughout the week, the local shop, Nook’s Cranny, will buy them from you at a price that changes once a day, at noon. And the price can really vary; usually anywhere from 40 bells to 600 bells.

To game the system and make more money, players buy as many turnips as they can on Sunday morning and then wait for a moment during the week when the price is high. But there’s a catch: if you don’t sell your turnips by the following Sunday, they rot and become worthless. So you’re desperately trying to sell them at a good price before your investment is completely wiped out. How different is that from the s-t-o-c-k market?

That sounds more like commodities markets. The commodity futures markets started in the late 19th century when farmers wanted to hedge out the risk that they had on their crops. So they would “sell forward,” meaning they would agree to sell a certain amount of grain or slaughtered pigs at some point in the future. The contracts would be literally say, like, on this day I’m going to deliver you this commodity at this price. And once you set that, the value of that moves around and people start trading the contracts themselves instead of just the commodity.

Recommended for you

While the Stalk Market sounds different, it’s similar in that you have a day where you really just need to deliver these things by. And if there’s too much of that thing relative to demand, you’re not going to get much for it. So it’s somewhat analogous to trading futures.

If you see what happened recently to the price of oil, once we all stopped going anywhere the demand for oil went way down. Oil storage actually ran out, and the price just crashed because there were a lot of people who needed to deliver the oil by a certain day.

Right — you’ve got all this stuff (in this case, turnips) and they have to go by this one day or they’re worth nothing.

Yes, exactly. And the reason that the oil price crashed so precipitously is that there weren’t enough places to even store the oil that was delivered. So people had to actually pay other people to take the oil away, because they couldn’t actually hold it.

The engine that drives the story of the game, such as it is, is a mortgage that you’re paying down. You start by living in a tent, and then you acquire a house, which can be expanded for additional mortgage payments. But in this mortgage there are no down payments, there’s no interest, and you can never default on it. You just have to pay it off before you can get your next expansion.

Well, I mean it’s great that there’s free housing, right? I think the thing the game does well is that it recognizes something a lot of people don’t get, which is that housing is mostly something you consume rather than an investment asset.

The way zoning laws have been developing recently, you have people who own houses setting up the rules at the expense of people who don’t, and so the value of the houses is going up more than incomes are. But if that wasn’t happening, there’d be other ways to organize society, right? But what a house really should be is just a thing you consume, and everyone has one for a reasonable price. The weird thing about Animal Crossing is that there is no price. That’s where the analogy breaks down.

Interestingly enough, you can’t sell your house in the game. So in that sense it is purely consumable. It’s not an investment. You’ll never get your money out of it.

Right. You’re stuck on your island!

Finally, the easiest way to make money in the game is that every day there’s a special glowing spot on your island. If you dig it up, you make a little cash, but more importantly, you can plant a bag of bells there. And if you plant 10,000 bells, a few days later, a tree will be there in that spot that has money growing on it.

Sounds nice!

Money literally grows on trees, is what I’m saying.

I guess the analogy is, you give up some consumption today and you get more tomorrow. In the real world, the amount you get is based largely on the amount of risk you’re taking. That’s why stocks have higher expected returns than bonds, which have higher expected returns than cash. But the notion that you’re tying up your money and getting paid, that’s a lot of what investing is.

Right. But it still doesn’t grow on trees?

I mean, not that I’ve seen.

That’s what they tell me, at least.

Well, if they know where the tree is, they don’t want you to know.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.