Money Diaries

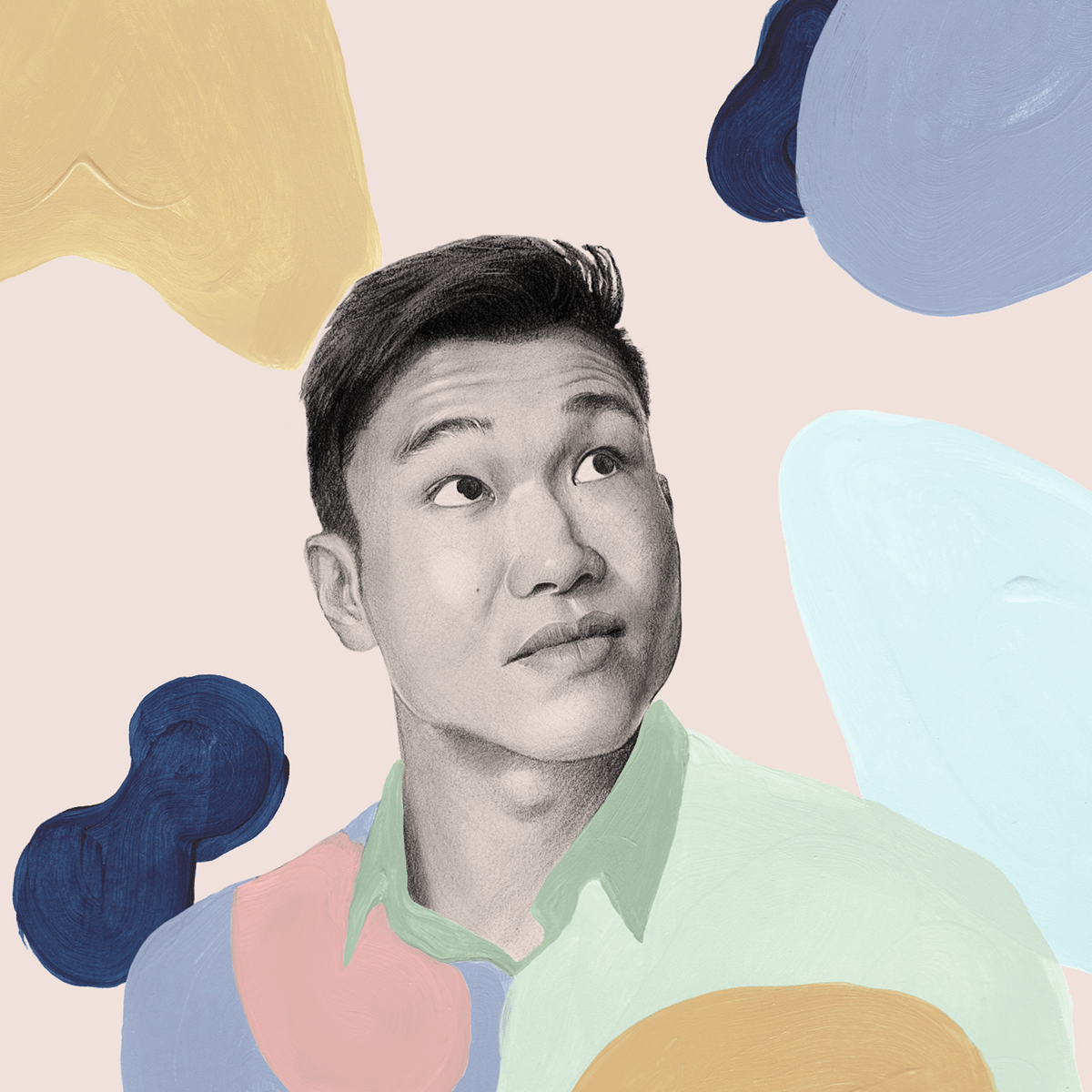

Friends with Money: Comedian Sam Jay

In her interview series Friends with Money, playwright and writer, Tori Sampson, talks to people she knows (and some she doesn’t) about money, what it’s like to have it and to be without it. Here, in her first installment: stand-up comedian, Saturday Night Live writer, and star of the Netflix special “Sam Jay: 3 in the Morning”, Sam Jay.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

I have always been fearful about – and obsessed with – money. I grew up with little financially and I’ve pretty much always surrounded myself with friends in my socioeconomic bracket, even as that bracket has changed. I think that’s usually just how the cookie crumbles. But then guess what? Some of my friends’ careers popped off and they got rich. I mean rich. I’m talking new money.

So, in true Sagittarius form, I like to do the taboo thing and ask my newly freed-from-Sallie-Mae friends to talk to me about it: their bizarre journeys, what it’s like to get real money, and whether it changed how they thought about themselves. Basically: the truths about how money works that I wouldn’t have known. Then my friend at Wealthsimple asked me if I would start recording those conversations. I said yes because I truly believe in the power of financial transparency. And because they paid me.

Money makes the world go ‘round and yet we’re made to believe discussing money is somehow uncouth? Fuck that shit. Tell me where you got those shoes from, girl!

P.S. I hate telling people where I got my shoes from.

—Tori Sampson

Tori Sampson: I bet a lot of people are going to look at you and think, this woman made it. I want to do what she did. What’s your advice on that?

Sam Jay: Look, I went through the grind. From the bottom. Started at open mic: take three minutes, build five minutes, [then] build ten. Turn bar shows into college shows. But, this is important, my way is not the only way. Like, you could go to school for this shit. I didn’t even know that. I had no idea. I just thought you had to be lucky and as funny as fucking Martin Lawrence. And it’s like, that’s not true.

I didn’t understand that National Lampoon and all that shit comes from a group of writers from Harvard and a thing called the Harvard Lampoon and that these motherfuckers get tracked into comedy writing and tracked into this whole career. And n—s is just hopin’ to get lucky. That’s crazy.

It’s like, damn, had I known that as a high school kid watching all of these comedy shows and sitcoms — watching Jackass and loving any type of comedy content I could find – if I knew you could go to college for that, I wouldn’t have went to school for fucking communications. I thought communications was the closest thing to what I wanted to do. It is the furthest fuckin’ thing from what I want to do but I had no concept.

So it’s like, we don’t really be knowin’. You know what I mean?

In your experience, have there been a lot of Black writers to come out of the Harvard Lampoon or places like that?

No.

It’s very polarizing: where people come from and how they enter the world and the knowledge that you get about how to get into this thing. It is not surprising that a lot of Black writers are like, “Nah, I gotta grind, I gotta do the Sam Jay method,” because that’s how we do.

Right and it’s like no, you don’t. You really, really don’t. And I don’t want people to believe that. And I don’t take pride in it. I hate this whole thing that people try to present like, “Oh, you made it despite the odds and da, da, da.” I think that we as Black people have been stuck in this rhetoric of, “That’s a bragging point for us, right?” Nah, fuck all that.

I’m not bragging about that shit. That shit is trash. And I would’ve rather had all the stuff. Where would I be right now if I had the stuff? Let’s talk about that instead of trying to make me one super n—. No, that’s not it.

Is money even real? I'm at a place where I don't even know if money is real, the way I see it thrown around.

Let’s back up. So we might not have known each other but we’re both from Boston. I grew up by Forest Hills and Roxbury.

What? I grew up in Dorchester and Roxbury. Like, the north fork side of Dorchester and then the Dudley side of Roxbury.

I went to Mission Hill for middle school.

I did too. What year did you go to the school?

I was there from ’01 to ’03.

Yeah? Right when I left Mission, you was there. You know my ex-boyfriend’s mother, Marla Gaines, the person that worked in the office.

Yes, I know Marla.

Yes, that’s my ex-boyfriend’s mother – Ed’s, not John’s.

Dang! I love Boston. Especially Black Boston, which nobody talks about.

Yes. I get asked about Boston a lot, but it’s like you can only really have this type of conversation with a Bostonian. I always say Boston has some of the most intellectual ‘hood n—s you will ever meet in your life. You’re supposed to have a certain level of intelligence and quickness, and that’s just an expectation. You can’t just be movin’ around here stupid.

A lot of times, even in my comedy, people will be like, “You’re so intelligent and so matter of fact, but so smart.” I’m like, “I’m just talkin’ like a Boston n—.”

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

So who did you grow up with in Boston? What was your family life like?

My whole family is from there. I was born in Georgia, but I was a baby. I don’t even remember Georgia. I came back to Boston before I was a year old.

My grandmother had 11 kids, so I have so many cousins. I was one of those kids who had so many cousins that I didn’t feel like I needed friends. I didn’t care if people at school liked me.

I grew up in Dorchester just doing Dorchester kid shit; running the streets, throwing rocks at cars, riding bikes, going to the YMCA for a free swim – bringing your little two dollars, so you can get you a slice of pizza, a .25 cent juice, chips, and some candy afterwards. It used to be that. You straight, you had a whole joint off two dollars. You was like, “I’m good to go.”

What did your parents do for work?

My mom was a respiratory therapist and my dad worked at UMass in computers. He was one of the first IT dudes that I ever met in my life.

When you were younger, were you inspired by that? Did that offer you some sort of stability to have these two parents with legit jobs?

They don’t ever pay Black people right, and I don’t think people really realize that but it’s real. ‘Cause those were two really decent jobs and we were still poor. We were still living in Dorchester.

When you’re thinking back to your childhood, what was your dominant perception of money?

It was just something that there wasn’t enough of. And it was always something you was chasin’ to get. I was well taken care of and I didn’t want for a lot. I do remember that. Like, if I asked for something, I got it. I was one of those kids. I had all the video game systems, I had all the toys. Kids would come over to my house to play. I never thought there was something I wanted that I couldn’t get.

That was before my mom died, my parents died, then everything changed again.

When you’re broke and Black, you’re being denied access on two levels, right? One of those chains you can bust. You can’t stop being Black, but you can try to change your financial situation.

Another thing we have in common is [that] both of our moms passed away in our teen years. Can you talk to me a little bit about your mom?

My mom was amazing. I talk to people whose parents are still alive and I’m like, I got more from my mom in that 16 years than they are getting now. So super, duper grateful. She was a very strict parent in a lot of ways, but not in a lot of [other] ways.

But when it came to character, and behaviour, and how you treat people, she was very serious about those type of things. She was one of those people that people always depended on. She was the glue to the family. It was one of those houses where whenever cousins got in trouble and got kicked out, they would come to our house. That type of a mom. And you would treat them like a brother. You weren’t to treat them any differently than you treated your own brother. I don’t know, she just taught me about how to be a good person.

You grew up with stability in the house, like the lights were always on, the phone was always on, that kind of environment?

Well, for a while. ‘Til my mom got sick and then she couldn’t work. And then sometimes the gas would be off for, like, two days or something, or the lights ain’t on when I’d leave to go to school but they’d be back on by the time I got home. So that’s when I kind of knew that financially my life was changing.

Growing up, I always would think about ‘90s sitcoms and I would imagine myself as part of that world. For me, it was Step by Step and Sister, Sister. I grew up with two sisters and a single mom in Boston, and we were definitely living paycheque to paycheque. I was really drawn to those sitcoms where a man would enter and it was like, “Oh, you movin’ to this new house!” Did you ever have sitcom dreams?

Yeah, I think so. I don’t know if there were specific sitcoms. I think I just would aspire to have a house. I thought that was cool. Like, oh, these people have their own house and they have a yard, yard. It’s just theirs, they’re not sharing it. Like, oh, they got a whole crib to themselves: upstairs, downstairs; it’s not just one level. [laughs] Two levels was impressive to me, ‘cause I’m an apartment kid. My whole life, I grew up in apartments. Even now, I think about getting a house but it’s kind of scary ‘cause I’m not used to living without people around me. The thought of a whole crib that I gotta be concerned about? Like, someone could come in at the bottom and I’m at the top. That’s crazy! I gotta watch five exits?

One of the things I noticed for myself is that when my mom passed away, I started to look at money differently. I started to be like, “Oh, I need to be serious because there is nothing to fall back on.” Did you have a similar experience?

I was still just blowin’ money. I was just bad at money. I was still like, you get money, spend it. Get one cheque, buy a Gucci bucket and be like, “I don’t know what I’m gonna do for the rest of the week.” [laughs] And be willing to sacrifice for the Gucci bucket. Fine, I just won’t have lunch for two days and be cool with that. I’m chillin’ but I am hungry though.

Because otherwise, you’re literally working to be able to work. The money you’re making is going right back into going to work. You gotta get bus fare or gas, you gotta have food for the week to be able to go there every day. Then you pay a little bit of rent and you’re back to zero. All the joy you have is being able to buy something. Buy some shoes, or go on a little trip, or go to the club and buy a little bottle. That’s the only payoff you’re getting ‘cause [the work] is not paying you off. It’s not good work for your soul or anything. And then people are like, “Nah, you don’t make enough to blow bread, you’ve gotta save that bread.” It’s like, “Well, then just kill me, dog.”

I was like, either I’m gonna be this type of person who’s just living paycheque to paycheque forever or I gotta make mad money.

People are judgmental but you have to find your riches, your joy, somewhere.

Right. It’s just not people being ignorant and they just want Gucci more than they care about their own lives. No. It’s: what is the point of any of this then? I’m already being told I’m at the lowest rung of life, [that] there’s not much potential for me. If all I have is this, and I don’t even get to have fun ‘cause I gotta squirrel this shit away for when I’m 60 and at the time I’m 20. It’s like, “What are you even talking about?”

That is the community. So you’re just gonna stay in the house while everybody else is doing that, then get up Monday and go back to work?

To the thing you hate. It’s like, nah, you gotta bring a good bottle. You gonna be like, “I brought the Henny Privy. Let’s do it, let’s do it!”

It's just not people being ignorant and they just want Gucci more than they care about their own lives. No. It's: what is the point of any of this if I don’t even get to have fun?

Exactly. So what was your first job?

I was 14, 15 and my aunt got me a good job. She was one of the few women [around] in construction, and the place was called Women in the Building Trades. It was a support centre for women that did construction and helped them get jobs. I was basically doing office, secretarial stuff.

But I ain’t wanna do that shit, so I wouldn’t go. My mom was livid. And you know Black families, when you’re young and you do something, it stays with you forever. So after that, none of my family would give me a job. Even when I was 23 and really needed a job, they was like, “No, you messed up that job.” When I was 15!

I think I quit – I just didn’t go back one day. I was notorious for that type of shit.

What’s the last job you did before you were like, “I’m committing to comedy?”

My last job was another little weird office job where I worked for a shipping company that tracked sperm around the country. Like, when people [find] their donors and stuff, and they gotta get [it] sent. The sperm clinics, they’d be sending it in.

I never had a job outside of comedy that I gave a fuck about. I was like, “How much does it pay? What is it going to require of me? Is it going to really get on my nerves or can I suffer through it?” And that was how I would pick a job, you know?

And I just left that job. I just left one day and didn’t come back from lunch.

Well, you finish how you start. Do you remember the moment you went from looking at other people and you were like, “Dang they got money,” and then you look at yourself and go, “Oh, I got money?”

Probably two years ago. Probably a year into Saturday Night Live.

When I first got to New York for SNL, I still felt broke. And I’d gotten cheques at that point. The biggest cheque I got was like $35k, and I was like, “Oh, alright.” I never got ‘hood lucky. I never caught a case or no shit, so I had never seen that much money at once. But I still was like, if this ain’t happening consistently, I’m kinda broke.

Anyway, I was in New York for a year, but I was still broke ‘cause New York is New York and I wasn’t sure if I was gonna get fired from SNL. The first year you’re on a show, they can just fire you whenever. Honestly. [It’s] kind of like, whenever they wanna say, “Hey, don’t come back after Thanksgiving,” they can and you’re just fucked ‘cause you don’t get that payout. That first year, they don’t have to pay you out for the contract if they just [want to] be like, “We’re good on you.”

So I’m in this little, small apartment in East Harlem but I know I’m not broke how I used to be broke ‘cause I could pay for this shit. Which is crazy. There are probably people who’ve lived like that their whole lives, so they’re like, “What?” But for me that was, like, big.

Yeah, for sure. People who are like that their whole life, I mean, good for you. I don’t know where your struggle comes from but sure. What’s the worst comedy thing you ever did for money or the worst paying job you ever did in comedy?

Oh, for money? You know what? This is gonna sound like I’m trying to be braggin’ but I’m not. When I got into comedy, I told myself I would not do anything for money. That money would never be the motivation for why I do something. [For] a lot of shit, I would say yes and then I wouldn’t even know how much it paid. It was, this is gonna grow me as a comic or I’m gonna learn something here or I need stage time.

I was like, I don’t want this to feel like the other shit I do for work. I don’t care if I’m broke ‘cause I’m already broke and I love this thing.

How much did you get paid for your first comedy gig?

Probably $15 and a couple of drink tickets, like a bar show. [The] first time I got what felt like real money for a show was probably when I started getting $250 a show. And then I remember one of my mentors, Jonathan Gates, was the first person who put real money in my pocket. He put like $800 in my pocket on a show one time and I was like, “Oh, shit. That’s some bread.”

I went to SNL, not for money – I went to SNL because I thought I could learn something. I had never written sketches in my life [and] this is the top sketch place in the world. What a place to learn that skill, to become a more confident scriptwriter. Then you’re also learning production, ‘cause you walk your whole sketch through, you block it, you’re with a director, you pick the wardrobe, you meet with hair and makeup – you decide the whole thing.

So now I see wealth in this because I have a wealth of knowledge and I see all of these different things that I could do. Now I’m not just a stand-up and I’m not just a person that’s always looking for gigs; now I’m a creator. Now I can write my own stuff, and create my own stuff, and make my own shows. And in that, yeah, there’s potential for wealth.

I never had a job outside of comedy that I gave a fuck about.

Can you tell me a little bit about how money works in comedy? So there’s stand-up money, there’s SNL money, TV-writing money?

There are so many jobs. I think that’s one thing that I was so ignorant to and I do want young people to know. I feel like especially when you grow up in the ‘hood, you have one perspective of how to do anything, right? You’re like, “Martin. I wanna be a comedian like Martin Lawrence.” And that’s the only thing we understand. We see the biggest thing. “I wanna be a comedian like Kevin Hart.” And that’s the only thing we see.

No one is telling you there are many comedians whose names you don’t know, who are multi-millionaires who tour all the time; who are happy, who have good lives. There are people that write that you’ve never heard about. There are people that produce that you’ve never heard about. There are motherfuckers that work in comedy, that are agents in comedy, that make a lot of money and are quite happy. There are a million jobs in entertainment. The only job is not to be the person in front of the camera doing the thing. The only job is not to be the product. You can be a million different things. And if you’re good at the things and you like the things, they can all be lucrative.

I hope that people get that track that you just laid out. Thank you for that. So what would you feel like is the holy grail of comedy if you want to actually make money in it?

Just creating your own shit. I feel like the people that are making the most money are just in control of their content and they are content creators as much as they are performers. Because being a comic, it still is a job. When you work at a bar or you’re doing these comedy clubs, you’re just another worker. You’re just as much a part of the wait staff as you are a performer.

Okay, your Netflix special “3 in the Morning.” How does a Black woman get this Netflix special? We know everything that Monique was talkin’ about Netflix specials and it just created this narrative that Netflix doesn’t do Black women comedians like that.

I mean, I don’t want to say that her experience isn’t true to her. I’m just… that was not my experience. And that’s not to say, like, maybe what they paid me… they might be playin’ me on the pay. I don’t know. I ain’t never been paid for a fuckin’ special before, so they might be doin’ some shit. But in the same way that I feel like all of Hollywood and every place that you work does some shit.

But, I mean, it was just a long relationship. That’s the thing. There is no shortcut. And not every relationship is going to work out and that’s okay. I think a lot of times too, especially Black people, we get into this shit and it’s like, damn, we had to do so much to motherfuckin’ get here and then as soon as someone don’t bite, you feel like they’re playin’ or they’re frontin’ or fuck it.

Yeah, you’ve gotta have amnesia in this business, for sure. As a Black female comedian, are you surrounding yourself with other Black women comedians?

I don’t know. I think that kind of happens by default. In a way, comedy is just like, comedians are all assholes and it’s such an equalizer of a space that I feel like I end up around a little bit of everybody Black. But I would say my core group of friends are Black [men]. I hang out with Chris Redd, Jak Knight and Langston Kerman. Those are probably my closest friends.

So what happens when you’re suddenly in the world of people who have money? What’s the most bizarre thing that you’ve observed since you got to this level?

I don’t even think it’s one thing as much as it’s just crazy how comfortable they are with money. [laughs] Just even when I started hearing the numbers in Hollywood of like, “Yeah, okay, this is the budget, this is what we’re gonna give you.” And it’s like, “Y’all got this much money to just give me? Then how much money do you have?”

Is money even real? I’m at a place where I don’t even know if money is real, the way I see it thrown around. Before I had money, I would say, like, “Champagne problems are problems of people who drink champagne.” So the poor kid in me is like, that’s crazy. But the person in me now who makes things and works in production is like, no, you need that. That’s reasonable, that makes sense.

I remember when I was a kid, I was watching this episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show and Will Smith said [that] he’s terrified of being broke again, and he’ll wake up with the sweats, like, “I don’t wanna be broke again.” And he had made enough money in his career that that was actually never gonna be a reality. Is that a real thing for you? Is that a legitimate fear?

Yeah. Hell yeah. I’m telling you, I woke up, and I did that math, and I was on the phone with my agents like, “Yo, what’s up with this job? Did these people call back?” Especially when you been broke for real. Broke, broke.

I feel like sometimes white people are like, “Is everything about race?” But it kind of is in this weird way. And so especially when you’re broke and Black. You’re being denied access on two levels at that point, right? And then you break out of one of those. One of those chains you bust, the one you can. You can’t stop being Black, but you can try to change your fuckin’ financial situation and how you’re living. And you bust out of that one and you taste [what] freedom really is. You taste fuckin’ freedom! Goin’ back to bein’ broke is goin’ back to bein’ in chains.

Is that what money means to you: freedom?

Oh, it’s 100 percent freedom.

So walk me through this. Let’s use Netflix for example. You get a cheque and how do you manage it? Is it like, I put it under the mattress? Stocks, bonds, investments. Do you have a money manager? I mean, it’s not, “I’m gonna blow it on a Gucci bucket hat?”

Well, I’m still doin’ that. [laughs]

I have a business manager, a money guy, that knows where all the money comes from and pays all the taxes and puts the money in the right places where the money should go. But I mean, me, personally, I am still budgeting poorly. I was just talking about that. I still don’t feel educated enough about money and I keep saying to my girl, like, “I need to learn about money. I don’t want to be Warren Buffett but I wanna know some of the shit this n— knows.” I get it but I don’t get it. I think that would help. I think I spend ignorantly because I’m ignorant to it – to a degree.

White people are like, "Is everything about race?" But it kind of is in this weird way. And so especially when you're broke and Black. You're being denied access on two levels at that point, right?

Right now, the United States is having a moment. Or a movement. A lot of people are talking about abolishing systems built to uphold racial and class hierarchies, and one of those is capitalism. As a Black woman, what do you think about capitalism in 2020?

I was talkin’ the other day about this. It’s weird because we’ve all been raised in a capitalist society. So I’m a liar to say I’m not a capitalist, I don’t want money and I don’t want to be able to buy things I want to buy. And I’m just getting to the money and getting to buy the shit. So I was just talking to my homie. I was like, “It’s whack because it’s like, I hear what n—s are sayin’ but it’s also like, I just got to the plate and now you’re trying to say [that] all the fun stuff shouldn’t be? It should all go away?” Because I did grow up capitalist, and my ideas of fun and enjoyment are being able to spend money on things and do the things I wanna do.

But then there’s this other part of me that goes, I think the problem isn’t capitalism. I think the problem is that we, as Black people, have allowed ourselves to be caught in aspirational white things, and so we have never taken our money and did our own thing with it. And the times that we have tried, they have destroyed that. So we now just buy in, and we’re buying into a system that doesn’t give a fuck about us.

The system has been theirs from the jump. White people understand and we don’t. We just don’t get it. We don’t buy politicians. That’s the type of shit we should be doin.’ Rich rappers are buying teams. Nah, buy a politician. And they’re for sale. They are.

Did you always think like that or was that a thought you started to form once you started getting money?

I always felt that way but I didn’t really know what to do. There is something to the shackles, the mental shackles, of racism and slavery. I do think that as Black people, we have to be honest, and a part of us still just wants white approval. We just want them to say that we are the same and that we can have the same things. We want them to finally just really invite us in and be like, “You know what, we was trippin’. Y’all are capable.” And it’s like, they never gonna fuckin’ do that.

And there’s something broken in us that we need that. And we shouldn’t because we’ve seen what they are and we have seen how they perceive us. So it’s like, why would you even want that approval? But that’s the mental shit. And I think a lot of times motherfuckers are making decisions from that demon and they don’t even realize it. Where it’s like, “I’m gonna buy into the NFL, so now I’m at the table with the bosses.” But it doesn’t matter because there’s another table they’re not telling you about, brother.

If you had Jeff Bezos money, what would you do with it?

Honestly, if I that much money, I would be on some Akon shit. I would be trying to build a Black city. Or I would be trying to buy politicians. I think that’s why God made me wait to get money. Inside, like internally, I’m really like a white Republican but of the eighties. I would be on to buy these politicians. “Let’s get these shady building deals goin’.” [laughs] “Let’s rock it out. Let’s go.”

[Here’s] one of the things I’ve always [been] interested in: when you go out to dinner with rich white people and they don’t pick up the bill, even though they can afford to pick [it up] for everybody. Have you experienced that?

Mm-hmm.

Why do you think they do that?

I don’t think they think about it the way we think about it at all. Like, they’re comfortable with money. We’re not comfortable with money, so when we get it, we’re like, “No, it’s on me ‘cause I got it.” But they’ve always had money and they’re not gonna spend their whole lives paying for everybody’s food. That’s crazy.

Why should they? Everybody around them is okay. And they assume if you’re sitting there, you’re okay.

Damn, it really does blow my mind.

But I feel them. Why would they? What I’m saying is they are not in tune. But the thing is, you can’t feel embarrassed, you can’t let their money make you feel embarrassed for advocating for yourself and your pockets. I’d be like, “Hey, baby, I ain’t got it like that, so I’ll pay for mine.”

That’s a word. Don’t let their money make you feel embarrassed about your pocket.

Yeah, for sure.

Tori Sampson is an award-winning playwright (her recent play “If Pretty Hurts, Ugly Must Be a Muhfucka” was a New York Times critic’s pick) and currently writes for “Hunters” on Amazon Prime. She is a proud Bostonian and lover of all things Julia Roberts and AJ1 sneakers.