Finance for Humans

How Do I Diversify, Anyway?

You’ve probably heard this advice before: diversify your investments or else bad things could happen! Well, how do you actually do that smartly? And why should you in the first place? We’ve got answers.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

If you read enough financial journalism, you’re bound to come across advice to diversify the asset classes in your portfolio. Which is a jargony way of saying: don’t invest in all the same stuff, unless you like losing money. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater, the world’s largest hedge fund, has gone as far as to call diversification the Holy Grail of investing for delivering high and consistent returns. We’re not saying everyone agrees (Charlie Munger famously scoffed at the strategy), but conventional investing wisdom holds that diversification will steadily grow your portfolio while also helping it ride out market turmoil.

So, how do you build a diversified portfolio? It’s a good time to ask that question, because the 2023 FHSA contribution deadline is coming up, on December 31, along with that for TFSAs and other tax-advantaged accounts. And you’ll have to make investment decisions if you contribute. Let’s get to it:

First: what, exactly, is diversification? It’s a strategy for growing your wealth in an inherently risky world by investing in different types, or classes, of assets. The thinking goes: since you can’t know for sure which investment will do better or worse over time, the surest way to build wealth is to invest in myriad assets that (1) are likely to increase in value and (2) will perform well in different economic environments. Stick with us; it’s not that complicated.

[1] Invest in stuff that grows. If you kept all your money in the bank, it would be super safe, but inflation would slowly eat away at its value. Which is why people invest in assets that appreciate, or gain value — like stocks, bonds, and real estate. There are logical reasons why these assets appreciate, but it mostly comes down to being paid for taking on risk: investors buy assets in exchange for a future payment, knowing there’s a chance they might lose money. And since investing carries risk, it’s smart to…

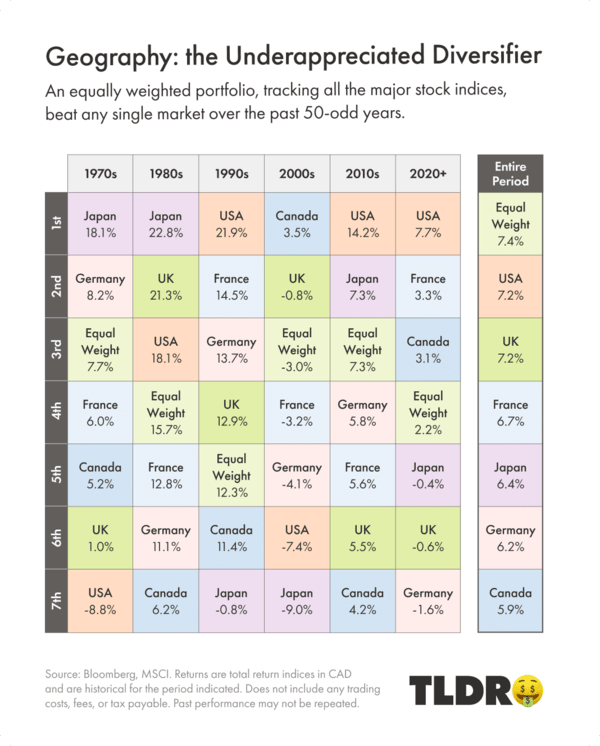

[2] Buy different assets, in different places. A big way to both mitigate risk and avoid missing out on good returns is to bet on assets that are geographically diversified. For instance, as the table below shows, U.S., Japanese, and Canadian stocks each dominated different decades over the past 50-odd years, but a portfolio tracking all the world’s major stock markets (“Equal Weight”) performed better than any one market — a big feather in diversification’s cap.

To maximize your odds of success — and that’s what diversification is all about — you probably shouldn’t invest only in stocks, either, because different asset classes perform well at different times based on economic conditions. Bonds, for one, tend to perform well when economic growth suffers and stocks fall. Moreover, as this chart shows, some years cash or government bonds have performed the best.

[3] Consider your goals and risk tolerance. Here’s the hard/fun part: how much of each asset class — stocks, bonds, gold, etc. — should you own? Pros call this “asset allocation.” And it’s hard to be terribly prescriptive about it, because your strategy should hinge on your investment horizon, goals, and risk appetite. You might want to hold more stocks when you’re young, say, and more bonds when you’re older.

That said, a few well-regarded investors have offered up asset-allocation targets. The late David Swensen, who managed Yale’s endowment to great success, suggested a portfolio composed of 30% domestic (that is, U.S.) stocks, 15% foreign developed-economy stocks (e.g., Japan), 20% REITs, 15% Treasury bonds, 15% TIPS, and 5% emerging-market stocks (Brazil, India, etc.).

Disciples of Vanguard founder John C. Bogle popularized an even simpler structure: the three-fund portfolio, composed of 34% domestic (U.S.) stocks, 33% international stocks, and 33% domestic bonds. Then, of course, there’s the classic 60/40 portfolio, composed mostly of stocks that are offset by (ostensibly) lower-risk bonds. If you’re looking for more guidance, here are some general allocation models for Canadian investors based on risk tolerance. There’s no right answer — just wrong ones if a downturn catches you unprepared.

Ben Mathis-Lilley is a senior writer for Slate.com and the author ofThe Hot Seat: A Year of Outrage, Pride, and Occasional Games of College Football. He's also written for BuzzFeed and New York magazine.

The content on this site is produced by Wealthsimple Media Inc. and is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be investment advice or any other kind of professional advice. Before taking any action based on this content you should consult a professional. We do not endorse any third parties referenced on this site. When you invest, your money is at risk and it is possible that you may lose some or all of your investment. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Historical returns, hypothetical returns, expected returns and images included in this content are for illustrative purposes only.