Money Diaries

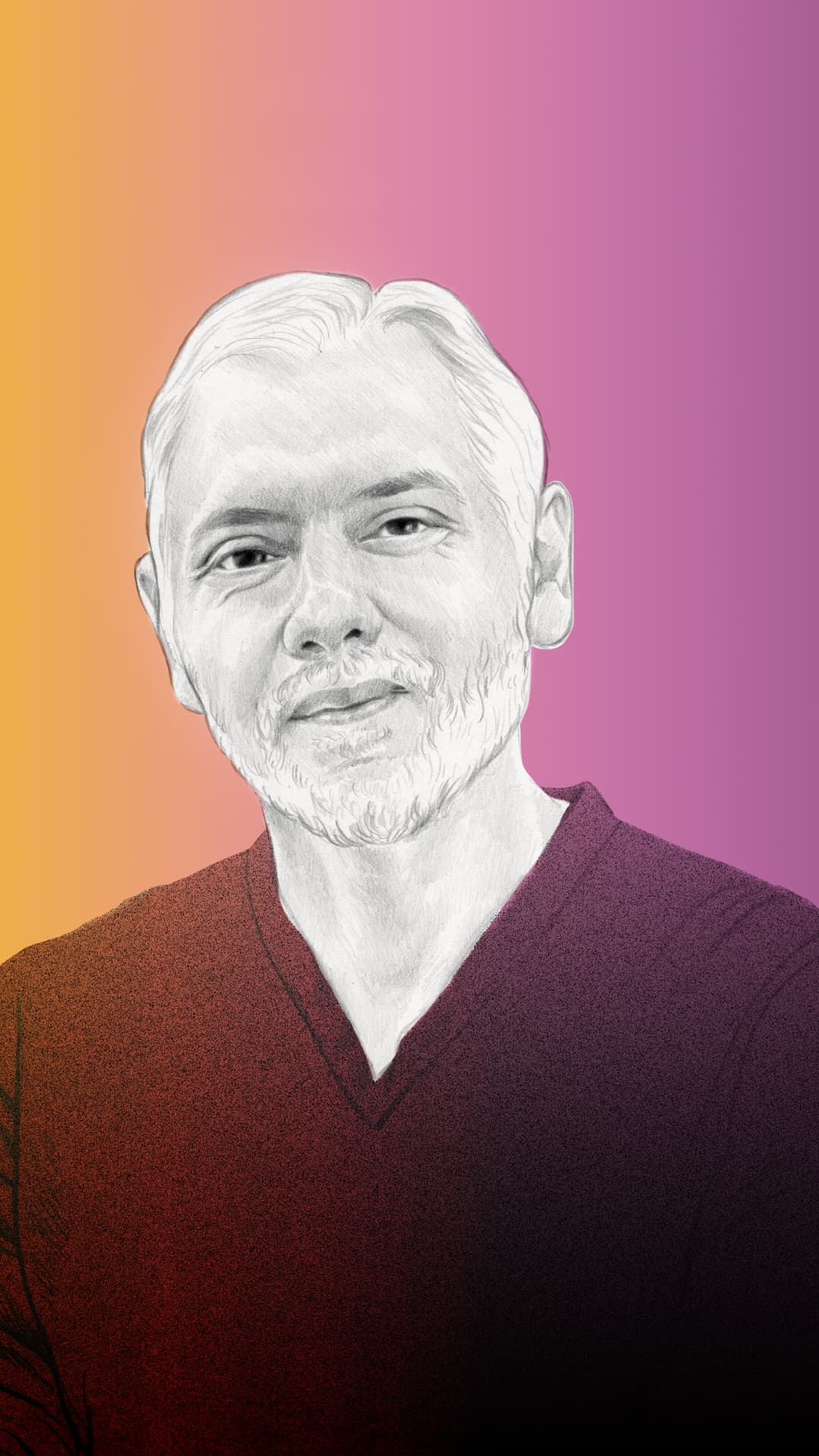

Novelist Omar El Akkad on Being the Engine and Being the Fuel

The Giller award-winning writer gives us his money story, from the inequities of Qatar to the inequities of capitalism.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

I was born in Egypt, in Giza, which is like the Mississauga of Cairo. My dad was an accountant, and. He specialized in hotels, so worked at the Cairo Sheraton for a while. Things in Egypt were awful — politically, economically — but by the time I was five, things were especially bad. Unless you were in the 1%, you couldn’t make much money, no matter what work you did. The elites were people who had effectively owned all of modern Egypt, and you couldn’t complain about it too loudly because you could veer into criticism of the government. It was not hyperbole to suggest that you might “be disappeared” one day. After an altercation with a couple of soldiers where he was lucky to get away, my father decided we couldn’t live in that kind of precariousness. Originally, he found work in Libya. My father has an incredibly common combination of names and, as we’re waiting at the airport, we learn that there was somebody on the terrorism watch list with his name. So we get taken in, we missed the flight, the job offer was revoked. A little while later, he got a job offer in Qatar, which I think eventually became one of the richest countries on Earth. So I ended up growing up in Qatar instead of Libya. Because of a coin flip at an airport.

At the time, the Sheraton was the only luxury hotel in Qatar, and that’s where my dad got a job. The country was in hyper-development then, and still is, because of the oil and gas reserves. My best friends growing up were a Somali guy, an Italian dude, and a Pakistani guy. Everybody was from somewhere else. I was part of this incredible mixture of human beings from elsewhere in the world. If you could turn your soul off, if you could turn off your conscience, it was the easiest life in the world. If you could look away from the endemic racism, and all of these fancy buildings and hotels being built by people from India and Pakistan and the Philippines, who were afforded no rights whatsoever. If you could turn a blind eye to the fact that everybody had a cook, a housemaid and a driver. A middle-class existence in a place like Qatar is like being in the 1% in the West. I thought it was the norm to grow up in a gated compound of luxury villas, where I could step out my front door and have access to an Olympic-length swimming pool at any hour. Once, one of my classmates told me he was staying in a hotel for a week because his parents were having columns of solid gold installed at home. One day, my father was invited to a conference of regional accountants from hotels in the Gulf. The guy who invited them had access to a private island, somewhere near Bahrain or Kuwait. They’re on this luxury boat heading toward the island. And my father sees butlers in the water holding canapé trays in full tuxedos, waist-high in the water. They were there so that if guests were swimming around and got hungry, they could stop to just grab a bite from one of these guys. Who had to stand there all day in the water in soaked clothes.

As I got older, there was a rubber-band effect. The grossness of that kind of life has put me in a place where I really don’t ever even consider using money for anything decadent. I don’t care how much or how little my books sell. It’s very much an emotional and psychological immune response to realizing what kind of a life I had. I’m never going to be a guy who goes out and gets a Maserati. When I was 16, we moved to Montreal and I hated Canada. I didn’t understand anything about the society. We didn’t have sidewalks in Qatar; nobody walked. We didn’t have public transit. Taxes were an entirely new and alien concept to me. And we didn’t have the connections in Canada that we’d had in Qatar. So suddenly we’re in a position where my dad is looking for work anywhere he can. A couple years after we arrived, I was heading to university and my dad found work in Chilliwack, B.C., at a resort. My mom went with him, and then they moved to Vancouver, then Calgary. My mom found work in Ottawa. Over the next ten or 15 years, they were moving a lot, almost always because they went where the work was.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

At university, I enrolled in a computer science program. All I’ve ever wanted to do with my life is write, since the age of five or six when I got a short story published in the school newsletter. It was the first time I realized that someone like me could, via this medium, reach into somebody’s head and move the wires around. But if you come from a particular part of the world, and a particular culture and particular class strata, the idea of becoming a writer or painter or musician is dismissed as not realistic. The immediate response would be, Oh that’s a great thing to do in your spare time. I thought of computer science as an area where I could maybe express some creativity and still meet the prerequisite of a reputable career. It took me an hour to realize there was no aptitude there. And I stopped going to class completely. I began to write for the school newspaper and it changed the trajectory of my life. My final transcript has a bunch of mercy 50s on it, and I got a 28 in statistics. I barely earned my degree.

After I graduated, I had enough of a portfolio from the campus paper and an internship at the Edmonton Journal to apply for a job at The Globe and Mail. They had a summer opening for an investment reporter. I had $4 and change in my checking account. The first day, my editor said, “We need you to do a web hit. Smith Barney has just issued a note advising its investors to bet on high beta stocks. We need you to write it up.” Half of that sentence was not in English, as far as I was concerned. At the end of the summer, they gave me another 10-month internship, and then after that they hired me full-time. If the Globe thing didn’t work out, there was no backup plan. It wasn’t like I was going to suddenly go interview at Google or something. For years after, I was based in Toronto and did two short stints in Afghanistan. I wrote about Omar Khadr from Guantanamo Bay. I ended up as the tech reporter for a while.

Recommended for you

She Was Living in a Shelter Six Years Ago. Now She’s the CEO of Her Own Beauty Company

Money Diaries

She’s a Toronto Legend, Model, and Style Icon. And She Was Nearly Homeless

Money Diaries

Alison Roman Is the Patron Saint of Home Cooking and Everyone’s at Home

Money Diaries

It’ll Work Itself Out (It Actually Won’t)

Money Diaries

When my wife, who did one of her post-docs at the University of Toronto, got a chemistry professorship at Portland State University, we moved to the States. I badly wanted to keep my job at the Globe: I paid for my own move, my own health insurance, I paid for everything. One of the defining aspects of my time at the Globe was this interminable sense of just being happy to be there, which I deeply regret in hindsight. I should have said no more often. I should have negotiated for what I was worth. Finally, they said, yeah, do it all on your own terms. They still had me classified as a business reporter; I wasn’t being paid as a foreign correspondent. None of it was on the books. I was just doing the work, roving the western U.S. writing stories. I thought, this is a dream job, I don’t care what the terms are. When the union found out, they objected, of course. The paper didn’t want to pay me as a foreign correspondent. And I realized they were never going to treat me in a way that was fair relative to what they were asking me to do. So I decided to leave.

I’d always written fiction, mostly between the hours of midnight and 4 a.m. I had no kids at the time, so I could do that. I wrote three novels while I worked at the Globe; all horrible. I sold the fourth one, “American War,” thanks to a bad day at work. I’d met an agent at a party years before, and after an especially frustrating phone call with newspaper management, I pulled up the draft I had of “American War” and emailed it to her. Three days later, she wrote back with an editor in mind. And a few months after that, he bought the manuscript for $200,000. I thought I was being pranked when my agent told me that. I thought, Oh, I’m set for life. Of course, then I learned it got paid out in quarters, and had to cut out 15% for my agent. So, before taxes, my new salary was about $45,000 a year.

There is absolutely no continuity or evenness to this kind of life. If it wasn’t for my wife having a stable day job, there is no way I could run a grown-up life on this kind of financial set-up. I don’t know how anybody lives off of royalties. There were years where I made $300,000 in royalties and combined rights sales, and there were years where I’ve made 5% of that — well below the poverty level.

Last year, winning the Giller Prize, it’s been life changing in almost every respect. The people I got to meet, to be mentioned in the same sentence as the other writers on the shortlist, I’m incredibly grateful for that. It also makes it more likely that we’ll be able to sell the next novel. Because there’s no paycheque coming in every other Friday, there’s no 20 people below me on the seniority list, I can’t go full Hunger Games on the situation if my employer downsizes one more time. For me, it was purely the relief of having a data point in favour of me being able to continue this career. But it’s hard to celebrate in any kind of overt way when you write books that are based on all the ways the world is going wrong, and are based on the misery we’ve allowed to be inflicted on our most vulnerable. You can’t then turn around and win an award and put on the party hat. The $100,000 prize money is still sitting in the bank.

I don’t generally agree with anything my characters have to say. But in “What Strange Paradise,” my most recent novel, there’s a human smuggler named Mohamed who says, “The two kinds of people aren’t good and bad, they’re engines and fuel.” I think we’ve set that up, as a result of the kind of society that we’ve allowed to exist. Not just capitalism or hypercapitalism; this insatiable need that we have for more. Gas consumption goes up as you floor it faster.

When I was a business reporter, I remember doing the Apple earnings story and the actual number didn’t matter in the slightest. It was the question of whether it was more than the same quarter the previous year. And I remember the notion of believing that we live in a world with an endless upward-pointing trajectory, as opposed to the possibility that we might be living in an umbrella-shaped world and we might be near the apex. It colours so much of what I write about, because I find it obscene that every serious institution that we have is predicated on an unending faith and this idea that there will always be more, and that we must always have more. And that requires endless fuel. And at a certain point, it creates conditions where you’re not getting better because you’re innovating, you’re getting better because you’re having those people who function as fuel become accustomed to making do with less. If we went back to our parents’ or grandparents’ generation and said, the new default mode of work is having 15 side hustles and you don’t get any benefits or seniority or health care, and if your car breaks down while you’re delivering Uber Eats, that’s your problem, they would have rioted. Our generation has been conditioned to accept that, and much more, and that freaks me out. That scares me.

Katherine Laidlaw is an award-winning journalist based in Toronto. She writes for WIRED, Outside and The Atlantic, among other publications.