Money & the World

Dumb Questions for Smart People: Teaching Our Kids to Be Financial Geniuses

Neale Godfrey — best-selling author and Executive in Residence at Columbia Business school — tells us how to teach our kids to be the money experts we never were ourselves.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

You literally wrote the book on teaching kids about money. How did you get into this subject?

I was president of The First Women’s Bank in 1985, and in 1988 I opened the first bank for children. It was in the toy store at FAO Schwartz: Tellers sat behind the counter, and the kids could make deposits and withdrawals from a real account. Princess Diana opened up accounts for the royal children. And I also opened up an Institute for Youth Entrepreneurship in Harlem, to work with at-risk children and bring them into the economy. But when I went to look for a book to teach my own kids about money, there wasn’t one. So, in 1989, I wrote Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees.

Why wasn’t there a book on this subject already?

We have this overhang from the Puritans that it’s not polite to talk about money. Here we live in the largest capitalist society in the world, and we’ve made money the biggest secret. We need to grow up and understand that money is not life’s report card. We need to teach our kids the values and life skills to live in the real world, and one of the skills they need is knowing how to deal with money.

How should parents begin teaching their kids about money?

The important thing is to talk in terms of values. It’s helpful to begin with chores. There are two types of chores. The first are “citizen-of-the-household chores,” which are personal habits, like brushing teeth and getting up on time and cleaning rooms. They should do these out of respect for everybody around them. But if you can afford it, you should also have a category of paid chores. These are simple skills that they’re going to need in life: doing laundry, vacuuming, recycling, dusting. I suggest that parents tie the child’s allowance to those chores.

How much allowance should we be paying our kids?

You can pay the child their age in dollars each week, and come up with a list of four or five chores they have to do. Then they learn the value of a job well done.

What if the child doesn’t do all the chores?

This is one of the most important values to teach them. If they don’t do their chores, they don’t get their allowance. When my son was seven years old, he was on Oprah with me, and he was telling her the chores that he had to do for his allowance. Oprah interrupted him and said, “Why can’t you do some chores and get paid some of the allowance?” I had never gone over it with him, and I thought, “Oh god, this is a train wreck.” But he just looked at her and said, “Well, Oprah, you can’t do just part of your show and still get paid.” I was like, “Yes!” Those are the values we’re trying to teach.

Why is that better than paying for each chore individually?

If you do it ad-hoc, they pick and choose what they want to do. That’s not the way it works in real life. I want to prepare kids for life. In real life, you have to do your whole job. But I always have odd jobs they can do for extra money, because I also want to incentivize them to earn more. So that could be washing sheets or cleaning up the attic or raking leaves.

How do you teach them to handle the money they earn?

Even a young child can manage a small budget. Budgeting is a word that people react to like a root canal, but it doesn’t have to be. It’s just a habit. Parents can teach their kids good habits very early. I recommend having four different jars or envelopes: 10% of the money they earn goes into the first jar. That’s for charity. Parents spend half their time saying to kids, “You don’t know how lucky you are.” My thing is, build that in. Teach them early that we are responsible for others. They can donate a few dollars to the environment, or sick children, or whatever they want to do. The remaining 90% is divided into thirds. So 30% is quick cash, which they can spend for instant gratification. They worked hard, so they get to make their own decisions with that money. The next third is medium-term savings: They push off instant gratification to save for something bigger. And the last third is long-term savings. It gets put away, so it starts soaking in that you don’t just spend it all.

Should parents contribute to their child’s personal savings?

If you see these little ones working hard and saving, yes. You don’t want them to be 43 years old before they can afford their first bicycle. So I recommend a matching plan, where you contribute dollar-for-dollar if they’re saving for something worthwhile. It’s about responsibility; it’s not about torturing.

Recommended for you

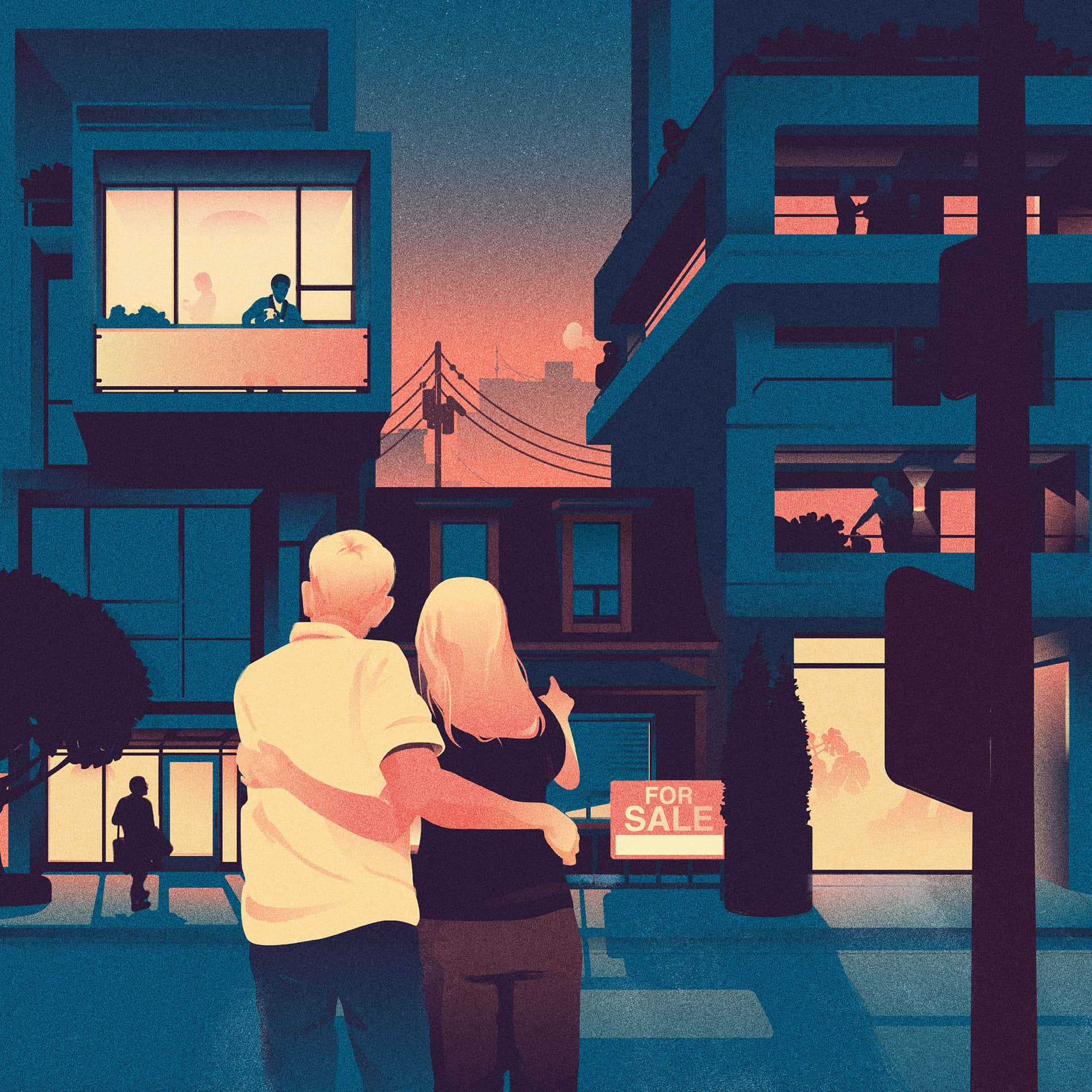

This Is Not Normal: A Letter From the Toronto Real-Estate Forever Boom

Money & the World

What’s Up With All Those Crypto Laser-Eyes Profile Pics? A Definitive Investigation

Money & the World

Canada’s Super-Secret Plan to Soar Past the U.S. Economy

Money & the World

We Discovered the True Identity of the NFT Artist “Pak”

Money & the World

How should they manage their long-term savings?

As long as it’s earned money, a Roth IRA (which is similar to a TFSA in the United States) for minors is great. I opened an account for each of my kids to save money they earned when they were very young, and my son is now 32 and he has several hundred thousand dollars in it. He’s a social entrepreneur now. He’s helping farmers in India and doesn’t make a ton of money, but he doesn’t have to worry about his retirement. He will have a couple of million dollars from the money he put aside when he was young.

Do you worry about kids becoming overly focused on money and savings?

If they are exhibiting fears around spending, you should intervene. We all know people like that — the check comes after dinner, and they go, “Oh, I only had the salad. And you know what, I don’t have my wallet….” If you hear your kid saying, “Go to the movies without me; I’d rather save the money,” then intervene. You want them to have a healthy balance between saving and spending.

As your kids get older, how can you give them more financial control?

You can let them manage part of the household budget, like the money you spend on their school supplies and clothing. Sit down with them on a quarterly basis. Let them write down what they think they need, and then go over it with them. They're going to come up with some astronomical estimate, and you say, “No, you don’t need five pairs of designer jeans.” But it helps them take more and more of the responsibility.

What do you say to parents who are in financial trouble themselves?

In an ideal world, it's wonderful to model behavior. But you don’t have to be in perfect financial shape to teach your children these skills. With our kids, there is the chance for a do-over. A parent who is overweight would never say, “I don’t care that my kids are candidates for obesity.” Nobody would say that. And while you’re teaching financial habits to your children, you’re going to learn good habits, too.

Is the money world any different now that it was when you wrote those books?

The digital world makes it more difficult to teach children financial habits. It’s really, really easy to spend money now. In a cash society, just 15 years ago, you had to spend physical dollars, and when you ran out, that was it. But with credit cards and online shopping, you can buy things with money you don’t have — and you don’t even have to leave the house.

How do you deal with that? Are there tricks?

That’s why I still like to start kids with real, tangible cash, so they can learn good habits before they gain access to online shopping and digital accounts.

How should parents talk with their kids about the cost of college?

For most parents, the cost is a challenge, and you have to come clean with them about it. This is a two-way street. If you can’t afford four years of private college, you say that up-front. You don’t wait for them to get into the college of their dreams and then say, “I can't afford it.” You say, “Let's talk about a budget.” Maybe you suggest community college for two years, and then a state school. Or they can take AP courses, or enroll in some online courses. Maybe they have to take out loans, but that should be proactive, not reactive. You say to them, “Maybe you don’t want to graduate with $150,000 worth of debt — let’s talk about what that means.”

It sounds like your overall philosophy is to give kids as much responsibility as possible.

If we can teach our children to earn what they need, to save what they can, and to live with their means, it will change the dynamics of the nation. The benefit of financial responsibility is obvious at the personal level, but on a societal basis, it also creates accountability. That’s really what you need at the macro level. We want our children to become adults who are capable and accountable.

Wil S. Hylton is an American writer. His last book was VANISHED.