Mutual funds have been the dominant player in the personal investment world for decades. There are over 5,000 mutual funds available in Canada. Here's a primer on what they actually are and how you can buy mutual funds.

What are mutual funds?

A mutual fund pools money from a set of different investors in order to invest in a portfolio of asset classes like stocks and bonds. Unlike the stock market, in which investors purchase shares from one another, mutual fund shares are purchased directly from the fund or a broker who purchases shares for investors. One of the most popular and common types of mutual funds tend to be equity funds, which invest in stocks, including Canadian equities and small or large cap businesses. Other common mutual funds include money market funds, which invest in short-term fixed income securities such as government bonds or treasury bills. Fixed income funds are another fund type that focus on investments that pay a fixed rate of return like government bonds, investment-grade corporate bonds and high-yield corporate bonds.

The price of the mutual fund, also known as its net asset value (NAV), is determined by the total value of the securities in the portfolio, divided by the number of the fund's outstanding shares. This price fluctuates based on the value of the securities held by the portfolio at the end of each business day. Mutual fund investors don’t actually own the securities in which the fund invests; they only own shares in the fund itself.

In the case of actively managed mutual funds, the decisions to buy and sell securities are made by one or more portfolio managers, supported by researchers. A portfolio manager's primary goal is to seek out investment opportunities that help enable the fund to outperform its benchmark, which is generally an index such as the S&P 500. One way to tell how well a fund manager is performing is to look at the returns of the fund relative to this benchmark. While it may be tempting to focus on short-term performance when evaluating a fund, most experts will say that it's best to look at longer-term performance, such as 3-year or 5-year returns. However, always keep in mind that any past performance is no guarantee for future performance. It's also worth comparing the alternatives to mutual funds which often have just as good performance and lower fees.

How to invest in mutual funds

The mutual fund industry is a service industry, and just as McDonald’s doesn’t camouflage their restaurants with shrubbery so only the hamburger cognoscenti can locate them, mutual funds make their wares exceedingly easy to purchase. So easy, in fact, that it falls to consumers to be fine-print scrutinizing critical shoppers. As you know, if you've ever received a Snuggie under the Christmas tree, companies are willing to sell you just about anything. There are currently over 9,000 mutual funds on offer in the US alone by one count. So do your homework to make sure you buy the absolute most appropriate mutual fund, and not find yourself saddled with the financial industry's answer to the Snuggie.

1. Select the mutual funds you want to invest in

Before we arm you with the tools to buy a mutual fund, first make sure it's the investment product you absolutely want to buy. Most mutual funds, fail to outperform the market, charge higher fees than other investments like ETFs and then often don't come with advice, unlike an automated investing platform.

If it's mutual funds you've settled on, the big online investing platforms — you know their names, they don’t need our help advertising — may offer a plethora of funds from a variety of fund families. Here's a guide to the various companies that manage and sell mutual funds, arranged by how much money they have under management. Bigger is not always better, so do your checks.

The biggest decision you'll make in buying mutual funds is deciding the sector that the mutual fund will invest in. American companies with large market capitalization? Small cap foreign companies? Or perhaps you're looking to focus more on emerging markets? If these terms are like Greek to you then you'll probably need to do some more research. You should also think about your investment goals and what kind of risk you're willing to take on: If you're more risk averse, then a more conservative portfolio is probably right for you. If you're working with a long time horizon, then you may be more enticed to add some riskier funds.

Once you've figured out what kinds of mutual funds you want to buy, make sure they're good quality in comparison to other funds that do the same thing. Many fund companies will provide ratings from Morningstar, the mutual fund rating agency, right next to all of their offerings. These range from one to five stars, five being the best. As the company explains here, these are unbiased assessments of how well a fund's past returns have compensated shareholders for the amount of risk the fund has taken on. If a fund has 3 or fewer stars, best to look elsewhere. That being said, there are perks for buying all your mutual funds from one company or “family” of funds which might include no-fee trading and possible lower management fees of individual funds after you reach a certain investment level.

Popular mutual funds in Canada

Here's a look at the most popular mutual funds in Canada. We've stack ranked the most popular mutual funds based on how much money is invested in each one (AUM). All of these funds are domiciled in Canada and the amounts are in Canadian Dollars. The table shows snapshots of their performance and MER as of May 2020.

Name | AUM in Billions | 1 Yr Return | 3 Yr Return | 5 Yr Return | MER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC Select Balanced Portfolio A | 37.6 | 3.22% | 3.16% | 3.91% | 1.67% |

| RBC Select Conservative Portfolio A | 32.7 | 3.55% | 2.71% | 3.23% | 1.59% |

| RBC Bond Fund O | 21.4 | 8.21% | 4.71% | 4.41% | 0.03% |

| TD Canadian Bond Fund - O | 15.9 | 7.15% | 4.45% | 3.90% | ? |

| RBC Select Very Conservative Port A | 13.8 | 4.03% | 2.67% | 2.91% | 1.45% |

Performance changes by the day and sometimes fees change too. You'll be well-served doing some further research about each of these funds before investing as much as a dollar.

2. Pick the right investment provider

Unlike stocks, which aren’t generally marketed and sold by the company’s themselves, you can go straight to the mutual fund issuers and buy their wares. These are referred to in the biz as “proprietary” funds. You’ve probably heard of companies like Fidelity, Vanguard and BlackRock. This very moment you could go directly to any of their websites and buy a portfolio of their propriety, or a branded, mutual funds. What you’ll understand if you ever strolled into Burger King and tried to order a Big Mac is that these companies really want you to buy their funds, not someone else’s. Fidelity, for instance, sells a select few Vanguard funds but charges you a significant fee you wouldn’t have to pay if you went to Vanguard directly. Smart investors generally go out of their way to avoid unnecessary fees (more on that a little later).

If choosing and buying mutual funds yourself already sounds like a too much effort, open an account with a robo-advisor. They'll invest your money in a whole platter of stocks, bonds and real estate, through various mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. Some robo-advisors provide handy services like financial advice, portfolio rebalancing to ensure your investments never go off course and tax loss harvesting to reduce your tax bill when investments go sour. It's an alternative to the DIY option which won't be for everyone.

3. Watch out for fees

Next figure out the fees charged. They are normally listed online and in the mutual fund's "fact sheet". Fees are like investment termites—they'll eat into your returns should you let them. Over time, fees can have a big impact on your returns. Let's say you put a cool $100k into a mutual fund that charged the average fee in Canada—you'd be a whopping $25k worse off in ten years. Had you invested that money in passive ETFs or with a robo-advisor that charged a fraction of the fees and achieved the same return.

Neither mutual fund companies nor online trading platforms are in the in business for the good of their health — they need to make money. So exactly how do they make it? They charge fees in the form of trading fees, management expense ratios and loads. Here's an overview of each type of fee.

Trading fees: Online platforms will generally assess a one-time trading fee to buy most mutual funds. Paying $50 dollars is not unusual. This can be a little or a lot depending on how much you’re investing. Since many mutual funds have no minimum investment, if you’re a new investor with $500 to invest, fifty bucks obviously represents a huge 10% right off the top. If you’re investing $10,000, it still represents a not-insignificant 0.5% of your investment. Increasingly, platforms offer pretty substantial lists of NTF (no trading fee) funds. If you’re dealing with the industry biggies, there shouldn’t be any hidden fees associated with these — other than MERs of course. So what the devil are MERs?

MERs: MER stands for Management Expense Ratios, and it’s how much the fund assessed every year to operate the fund. Mutual funds are run by fund managers, highly educated math whizzes entrusted with trading the contents of the fund based on whether they foresee the value of the fund's investments going up or down. The fund managers have assistants and the company spends truckloads of cash marketing the funds with glossy fund pamphlets and tropical boondoggles for brokers. MERs are expressed as a percentage, and one that might look quite small, like 1 or 2 percent, but it’s important to understand this percentage is shaved off the value of the entire fund annually whether or not the fund made or lost money. Over time, these innocent looking MERs add up--way up. Check out how A 2% MER over 25 years can shave $170,000 off of the historically reasonable gains on a $100,000 investment.

Loads: It’s not uncommon for trading platforms to “waive” trading fees for mutual funds that come equipped with loads. Considering that load is just a fancy term for sales commission, there’s no waiving going on at all, they're just putting the fee in a different place. Loaded mutual funds are named based on when the fee is charged. Class A shares are “front-loaded” meaning they assess the fee just as soon as you buy the fund, B shares are “back-loaded,” meaning they'll charge a fee when you sell it, and C shares spread the fee over some, or the entire period, you own the fund, usually a period of a year.

4. Manage and rebalance your portfolio

Trading mutual funds should never be undertaken for emotional reasons. If the American stock market experiences a big tumble one day, emotionally, you might be tempted to move your money to cash or foreign stocks. According to the first rule of investing buy low, and sell high - this would obviously be the absolute worst thing you can do.

That said, you should plan to periodically adjust your investments to maintain a consistent asset allocation since inevitably some investments will do better than others and will become a disproportionately large part of your portfolio. Plan on rebalancing your portfolio annually. If you're math impaired and have a hard time following guides like this one on rebalancing, consider signing up with an automated investing service which generally does this automatically.

Alternatives to mutual fund investing

Most digital advisors and ETFs target the same returns as mutual funds but the fees as we mentioned the fees are much lower. This makes robo-advisors or exchange-traded funds a good choice for many investors.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs)

ETFs are kind of like a mutual fund’s cousin. They both help investors buy large swaths of investments in one fell swoop. And they both often concentrate those investments in a particular sector — be it stocks, bonds or real estate. But they have their differences, the biggest one being the price for entry — it's often lower for ETFs. You can start investing in ETFs by trading yourself or opening an account with an investment provider that will create an investment portfolio for you. Exchange-traded funds generally have lower fees than active mutual funds because you're not paying people to actively manage your money. ETFs are traded like a stock, meaning they can be bought and sold throughout the trading day.

Automated Investing (robo-advisor)

A robo-advisor is a service that uses algorithms to do the job of wealth managers who tinker with your investments over time. Many mutual funds require initial investment minimums that can be as high as a few thousand pounds. Most robo-advisors have low account minimums or no account minimum at all. This makes them much more small-investor-friendly. They're equally as valuable for large investors as generally, they have low fees and perform just as well. Fees eat into the amount of money you potentially make from investing and so you should seek to reduce them as much as possible. While actively managed mutual funds try to beat the market, robo-advisors generally use index ETFs that aim to track the market. Most have a fiduciary duty which means they have to put their client's interests ahead of their own.

The chart below compares a traditional financial advisor/mutual funds to a digital advisor/ETFs.

Disadvantages of investing in mutual funds

Since mutual funds are expensive and often only perform just as well as passive automated investments - there are lots of disadvantages. Here are five of the main ones.

Cost: Management fees of mutual funds tend to be very high. This eats into your returns.

Fees: May have built-in “loads,” which are essentially sales commissions.

Liquidity: Other investments may be traded throughout the trading day rather than only once per day.

Financial Advice: Most mutual funds do not come with advice. Often it's an additional cost.

Spotty returns: Over the long term, the vast majority of actively managed mutual funds have failed to outperform benchmarks. Many active mutual funds fail to outperform the market yet you still pay for "active" management.

Advantages of investing in mutual funds

The disadvantages of mutual funds will probably outweigh the benefits for most investors. That said mutual funds have advantages over some types of investing like individual stock picking. Here are a few advantages of mutual funds.

Flexibility: Able to react quickly to changing market conditions.

Diversification: A single mutual fund may contain dozens or even hundreds of separate stocks or issuers.

Liquidity: Mutual funds can be bought and sold once every trading day.

What does the letter at the end of a mutual fund name mean?

You've probably noticed there's a single letter listed in the name of many mutual funds. This refers to the series or class that the fund falls into. Each series has different benefits and a different cost structure.

A series: These funds are typically sold by a financial advisor or bought directly by an individual. Mutual funds with "A" in the name typically have a lower minimum investment requirement compared to other mutual funds. Advisors that sell A series of mutual funds may receive a commission for selling them to you.

D series: The "D" series are built for self-directed investors who buy the funds through a brokerage. No advice comes with D series funds and as a result, they generally have lower fees than other mutual funds.

F series: The letter F stands for fee-based mutual funds. The fees are removed from these funds as they are generally bought through a financial advisor. The fees are paid through the advisor rather than through the fund. Advisors often charge in the region of 1-2%.

I series: The "I" at the end of mutual funds can mean a variety of things. In most cases, it stands for institutional. It can also stand for "income" or "investor" series. Some I series funds have a high investment minimum making them suitable only for high net worth individuals.

O series: The letter "O" doesn't actually stand for a word beginning in O. Generally O refers to institutional mutual funds.

T series: Mutual funds with the letter "T" at the end will be tax-advantaged most of the time. These funds often have some portion of the returns that are not taxable.

How do mutual funds work?

Mutual funds are divided along four lines: closed-end and open-ended funds; the latter is subdivided into load and no load.

Closed-end funds: This type of fund has a set number of shares issued to the public through an initial public offering (IPO). These shares trade on the open market. This, combined with the fact that a closed-end fund doesn’t redeem or issue new shares like a normal mutual fund, subjects the fund shares to the laws of supply and demand. As a result, shares of closed-end funds normally trade at a discount to net asset value.

Open-end funds: A majority of mutual funds are open-ended. Basically, this means that the fund does not have a set number of shares. Instead, the fund will issue new shares to an investor based upon the current net asset value and redeem the shares when the investor decides to sell.

Load vs. no load: In mutual fund terms, a load is a sales commission. If a fund charges a load, the investor will pay the sales commission on top of the net asset value of the fund’s shares. No-load funds tend to generate higher returns for investors due to the lower expenses associated with ownership.

Paying attention to account minimums and fees can be an effective way to choose among mutual funds.

How to make money from mutual funds

With all types of investing that you can make money or lose money. Investing in mutual funds is no different. When you invest in a mutual fund, cash or value can increase from three sources:

Dividend payments: Income is earned from dividends on stocks and interest on bonds held in the fund’s portfolio. A fund pays out nearly all of the income it receives over the year to fund owners in the form of a distribution. Funds often give investors a choice to either receive a check for distributions or to reinvest the earnings and get more shares.

Capital gain: When a fund sells a security that has gone up in price, this is a capital gain. When a fund sells a security that has gone down in price, this is a capital loss. Most funds distribute any net capital gains to investors annually.

Net asset value (NAV): If fund holdings increase in price but aren’t sold by the fund manager, the fund's shares increase in price. This is similar to when the price of a stock increases — you don’t receive immediate distributions, but the value of your investment is greater, and you would make money if you decide to sell.

Investors in a mutual fund share equally in losses and gains. If one of your investments within the mutual fund goes bad at least this does not drag down your entire investment portfolio. While investing in mutual funds does help to spread the risk, it doesn't eliminate it. While it's possible you could make money from investing in mutual funds, you could also lose it.

Should you invest in mutual funds?

Truth be told, you often won’t have any choice in the matter as to whether you invest in mutual funds. Many retirement plans, such as RRSPs and TFSAs, as well as other tax-advantaged accounts such as RESPs, offer mutual funds among their investing options. And because of the insane-to-pass up tax benefits and employer matching funds, you should probably put as much of your salary as you can muster into these plans. So yee-haw mutual funds in this case!

If it comes down the choice between putting your money in one, two, or even five individual stocks or putting it in a mutual fund, you should consider investing in the mutual fund because of something called — diversification. With a mutual fund, one price will buy you positions in dozens, even hundreds of different stocks. Gamblers and stock pickers love to entertain audiences with stories of turning $100 into $10,000, but they loathe to tell you their stories of how many hundreds of thousands in losses it took until they hit their big score. When you spread your investments should one go sour, it won't drag down your entire portfolio.

Picking individuals stocks is a lot like playing the lottery with your life savings. The top best performing 4% of stocks accounted for the entire wealth creation of the US stock market since 1926 which means there were lots and lots of losing stock pickers. Think about it: when you’re buying a stock, you’re buying it from someone who’s selling. The seller has decided the stock is worth selling at say, $10 dollars a share because she's sure it's definitely going to go down, but you're sure it's definitely going to go up. Who’s right? What makes you so sure you’re so much smarter than that seller? For this reason, diversification is the answer. The more diverse your holdings, the less vulnerable you’ll be to unexpected stock or even sector dips. So, again, score one for the mutual funds. Yay funds!

But hold the phone for just a second. Just because mutual funds are better than investing in individual stocks, are they necessarily the absolute best way to invest your money? Maybe not. Those fees that we discussed above are the enemy of good returns; studies have shown over and over again that fees are directly predictive of returns in a very simple way; the higher the fees, the lower the returns.

But, you’ll naturally retort, those fees have to be worth it, right? The big brains who pick stocks in mutual funds must be able to justify their fees by their boffo returns, and all the people who earn fortunes managing mutual funds will swear that their expertise is well worth the fee you pay. Science begs to differ with their conclusion. In fact, most studies show that almost all actively managed funds will fail to outperform the overall market over the long term.

The alternative to mutual funds, aka active investing, is passive investing. Passive investing is basically leaving your money alone for a long period of time in a low-fee account that seeks to mirror, rather than outperform a market. This can be accomplished in one of two ways — either through a particular kind of mutual fund called an index fund, which tends to have significantly lower fees than actively managed funds because it simply maintains holdings in proportion to indexes, like the S&P 500 for instance.

But the product that’s made the biggest mark on the passive investment world is the ETF, short for an exchange-traded fund. Like mutual funds, ETFs are basically investment wrappers that allow you buy a large basket of individual stocks or bonds in one purchase, but unlike mutual funds, which are priced just once a day, ETFs can be bought and sold during the entire trading day just like individual stocks. Because they’re largely unmanaged by humans, ETFs (and many index funds) have fees that are a small fraction of those of actively managed mutual funds. These MERs normally come in at between 0.05% and 0.25%.

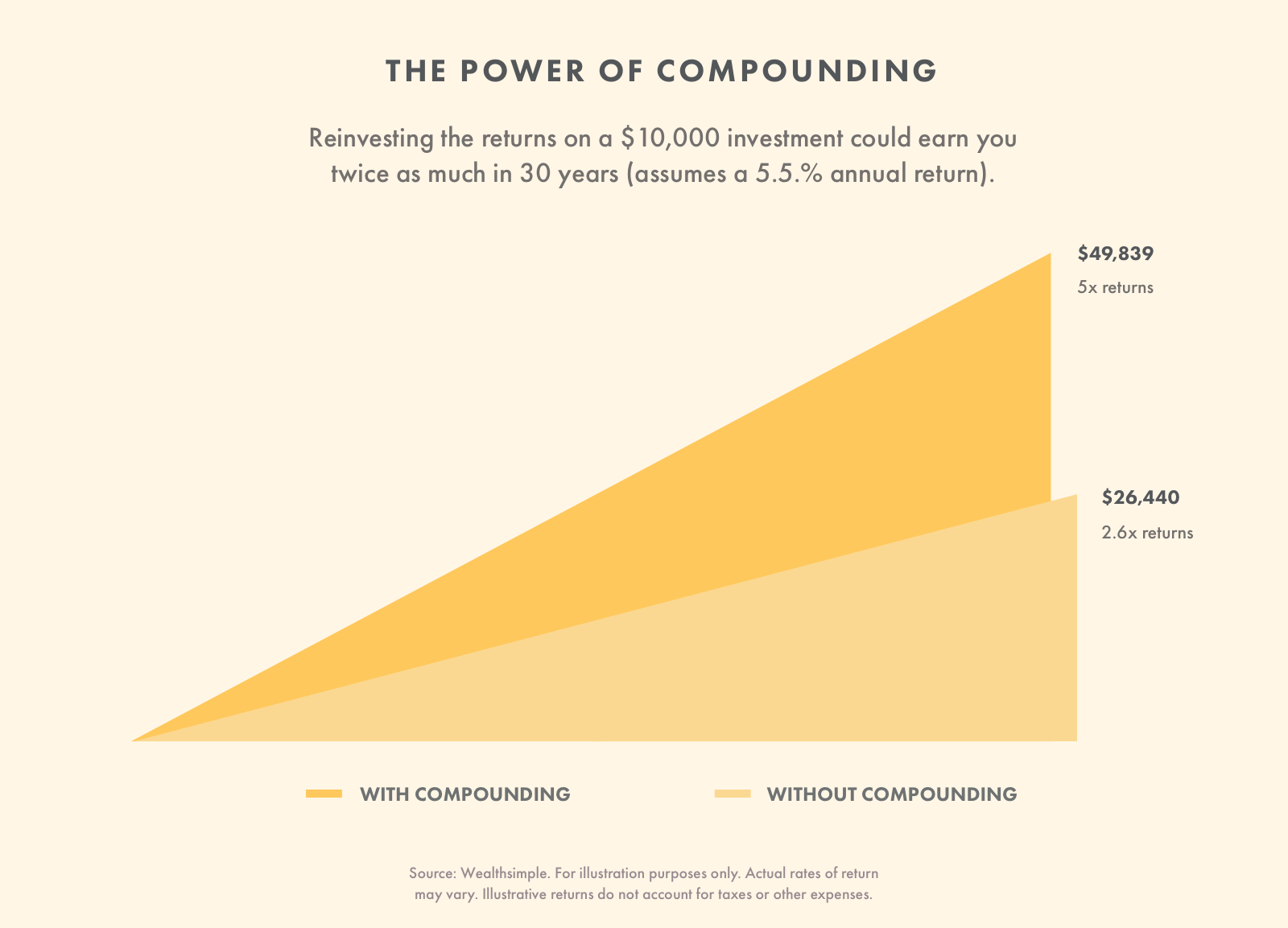

The long term benefits of a low-fee passive strategy are remarkable thanks to compound returns, which are basically returns on returns. Play around with a compounding calculator like this one to get a feel for what time can do to money that’s unfettered by fees. Between the years of 1950-2009, the stock market grew by 7% per year. So, had you invested $10,000 during that time, the miracle of compounding could have turned that investment into a cool hundred thousand in about 33 years. Automated investing services have sprouted up in order to guide both beginning and seasoned investors to plot a course to financial freedom through low-cost, highly diversified portfolios of ETFs.

Owing to the volume of research that favours a passive over active approach, there’s been a veritable geyser of money moving from active to passive management. A vocal minority of investors have warned that this rush to the exits by active investors has created new, huge opportunities for active investors to make a lot of money by zagging while the rest of the world zigs, and potentially devastating pitfalls for the passive horde. (Could there be an ETF bubble?) But the henny pennying remains purely theoretical, while the arguments for passive investment superiority has been thoroughly supported by history, notably in a landmark 2004 study undertaken by Vanguard. And since in pure dollars, mutual fund assets are far larger than those of ETFs, we probably have a long time before reaching the much warned about state of 40% of all investments passively invested, a condition that’s been dubbed “peak passive".

The truth is, nobody can say anything with any certainty. The only thing we have to go on is historical stock market returns; and you should remember that any stock market investment, whether passive or active, is speculative and there's always a chance you lose a good bit or all of your investment.

Certainly, a pretty good argument could be made for diversification in not only financial sectors and geographic regions, and probably dividing assets between both passive ETFs and actively managed mutual funds.

When to invest in mutual funds?

Wherever you ultimately decide to invest your money, our advice is to start investing as soon as you possibly can.

The most powerful tool you have is time, thanks to the miraculous power of compounding. It's what Warren Buffett calls the eighth wonder of the world and it could potentially make a little money into a lot more if you just give it time to grow.